- Home

- Peyton Thomas

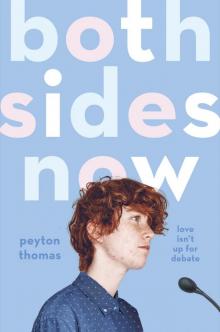

Both Sides Now Page 4

Both Sides Now Read online

Page 4

“So, okay, scale of one to ten,” Lucy presses. “How hot is Ari Schechter?”

“I . . . I can’t . . . I don’t know!” I splutter. “I don’t want to say something misogynistic!”

“What the hell is that supposed to mean?” says Lucy, looking at me the way she does when I say something misogynistic.

“It means I don’t want to rate her appearance on a scale of one to ten!” I yelp. “Can’t I just tell you how she looks?”

“Sure,” says Lucy, blowing a strand of pink hair out of her face. “I just wanna know if she’s my type.”

“Well, she has brown eyes. Brown hair. Short. Her hair, I mean. She’s not short. She’s tall. Not abnormally tall, though. Normal height.”

“Wow,” says Lucy. “It’s like I’m there.”

“I’m sorry!” I throw up my hands, defensive and baffled, equal parts. “I have no idea how to talk about girls! You’re still the only one I’ve ever . . . you know.”

“Ever what?” She chews on a mouthful of chickpeas, grinning slyly. “Held hands with?”

“Dated.”

She snorts. “Finch, we were, like, twelve.”

She’s not wrong. Our relationship ended about a month into the summer before eighth grade. In her bedroom, the door locked tight, I told her that I couldn’t be her girlfriend. She took the news well. She told me she loved me. She hugged me so hard I thought my bones might break. And then she told me that I couldn’t be her boyfriend.

“Well, I still feel like I’m twelve sometimes,” I tell her. “Especially when I listen to Jonah on the phone with Bailey. That conversation was just so . . . I don’t know, grown-up.”

“Okay. Radical idea here.” Lucy takes a careful bite of tempeh, and speaks slowly through it, crumbs falling from her mouth: “Given that this story involves you experiencing so much anxiety you can’t even speak to a girl, and ends with you getting so emotional about a guy talking to his boyfriend that you had to flee the premises, have you considered that you might be . . .”

“Lucy,” I groan. “Just because you’re gay, that doesn’t mean everyone else . . .”

“I’m just saying!” She throws up a hand, half a shrug. “Something to think about!”

I do wonder, just for a moment, if it is something I should think about. This isn’t the first time I’ve had this talk with Lucy. She’s fond of asserting—much like her hero, Kurt Cobain, once did—that everyone is gay. She tells a story about the time she told her mom she liked girls. The very first time. When she was five. She made her announcement, and her mom was like, “What about boys?” and Lucy thought it over, then answered, “No. Just girls.” Lucy’s mom, recently divorced and wary of men, threw a hand over her heart. “Oh, sweet pea,” she said. “What a relief.”

Me, though? I’ve never been that sure about who I love. The more important question, I think, is this: Will anyone ever love me?

Before I can fall too deep into a spiral of self-loathing, the bus driver calls out, “Next stop, Johnson Tech!”

Lucy rises. “This is us,” she says, helpfully.

“I don’t know. I might stay on for a few more stops.” I sigh, and slump even further into my seat. Not even eight o’clock in the morning, and already my binder is murdering my back. Surgery cannot come soon enough. “I’ll skip first period. And second. And third. Just ride the bus east into the rising sun.”

“Uh-oh.” Lucy hoists her canvas backpack onto her shoulders. “Behind on homework again?”

Every tournament, I tell myself: This one will be different. I’ll manage my time. I’ll balance my priorities. I’ll devise a color-coded Urgent/Important scale, à la Eisenhower, and follow it to the letter.

And every time, without fail, I fully ignore all my homework for the entire week leading up to the debate.

Well, no. Not “without fail.” There has definitely been some failure. Mostly in calculus.

“I really need to get it together,” I tell her as I stand and step into the bus’s narrow corridor. “If my grades tank this semester, there’s no way I’m getting into Georgetown. Or any of these D.C. schools.”

Lucy follows me to the door of the bus. “You know, you don’t have to go to D.C. to make an impact,” she says. “You could stay here. Work for a state senator.”

“But there’s no action here,” I say. (Okay, whine.) “I want to go to D.C. Where all the world-historical political fights are.”

“Why not go to Evergreen?” She’s talking about the granola-crunchy state college here in Olympia. “You know how many world-historical political fighters went to Evergreen?”

I shoot her a doubtful glance. “Name one.”

“Uh, Rachel goddamn Corrie?”

Okay. She’s got me there.

I spent most of my life being hopelessly confused about the whole Israel-Palestine thing. Then, last spring, the topic for Regionals rolled out: This House believes that the United States should impose sanctions on Israel. I went grumbling to Google to get started on research, and I found those photos of Rachel Corrie. The ones where she’s lying in the tracks of a bulldozer, blood streaming from her nose.

And suddenly, I wasn’t confused anymore.

“That is not fair,” I complain. “I’m nowhere near as brave as Rachel Corrie. I could never stand between a bulldozer and somebody’s home.”

“Well, could you stand in front of a home here in Olympia?” Lucy asks me, as the doors of the bus accordion open.

“What are you getting at?” I ask her, as we step onto the sidewalk.

“Denny Heck’s leaving Congress this year.” Lucy pulls the straps of her backpack tight over her shoulders. “My mom says there’s this really cool trans lady running to replace him. Alice Something. She came by Viva the other day with some brochures.” She shoots me a sideways smile as we reach the crosswalk. “If you stayed here in Olympia, you could knock on some doors for her campaign.”

I shouldn’t feel disappointed. But I do. “I want to be the first trans person in Congress.”

“Dude, you’re like, five years old,” says Lucy, rolling her eyes. “You don’t want anyone to get there before you?”

“Staying in Olympia to volunteer for a campaign,” I say, stubborn, “is not the same thing as going to college in D.C. so I can learn to run a campaign.”

“No. Not the same. Better, probably.”

“You would say that,” I huff, as the walk signal flickers and we cross. “You’re not even going to college.”

We have this argument every day. Lucy thinks college is a scam—a bourgeois scam, even, if she’s especially riled. I, on the other hand, think my life won’t start ’til I get to Georgetown. Neither of us ever budges an inch.

“I don’t need a degree,” Lucy says, confident. “I know how to edit videos. I know how to write scripts. I know how to turn on a camera. All I need is a Patreon, and I’m in business.”

She’s explained it to me before, this political-activist YouTuber thing. They call it “BreadTube,” I think, in reference to some obscure Russian philosopher who, I guess, wanted to give people bread? I don’t understand YouTube. I definitely don’t understand how Lucy plans to make a living through YouTube. I want to grab her by the shoulders sometimes, shake her, tell her, “You have to go to college.”

But I’m a good friend, and good friends don’t get into knock-down-drag-out brawls with one another. Not first thing in the morning, at least, with a long day of school ahead. So when I take her by the shoulders on the brick steps of Johnson Tech, all I do is squeeze, gently. I tell her, “I’m rooting for you.”

“I’m rooting for you, too, Finchie,” she tells me. “All the time. Always.”

And then she kisses me on the forehead. Nobody else gets to do that. Only her.

* * *

—

“There he is! Our

very own loser!”

On my way into debate club after school, Adwoa doesn’t just meet me at the door. She full-on tackles me—whipping her arms around me, rocking me back and forth.

“Get in here!” she bellows, even though my ear’s not even an inch away, as she hauls me into the cluttered history classroom that houses our club. “I made cake!”

She sure did. There, on the teacher’s broad desk, is a sheet cake almost the size of that desk. It’s coated in elaborate, every-color-of-the-rainbow icing. CONGRATS TO OUR LOSERS, it reads, the letters piped by an impressively even hand. How late was she up, baking this thing, frosting it? And how did she know that it was exactly the consolation prize my heart needed?

Well, not just my heart. My stomach, too.

“Drop out of law school,” I beg her. “Open a bakery.”

“I’d love to,” she says, giving me a spirited whack between the shoulders. “But litigation pays better.”

When Adwoa’s not coaching us, she’s wrapping up her last year of law school up in Seattle. Every Monday, after a long day of classes, she hops on a bus and rides down to Olympia to argue with us. She talks about moving on to a high-powered job at some big tech firm, like Microsoft, or maybe Amazon. She works hard, dreams big, takes no shit. She’s everything I want to be when I grow up—but trade Silicon Valley for Capitol Hill, and subtract the knife-point acrylics.

“Jonah? Finch?” She gestures with said acrylics, bedazzled today in silver. “You guys gonna cut this cake, or what?”

With one glittering hand, she passes me a butter knife; with the other, she beckons Jonah forward. The freshmen and the sophs part for him in neat, clean lines. When his hand closes around mine on the handle of the knife, his palm feels warm on my skin. Not sweaty; warm. Are my hands cold? Is that it? People tell me all the time I’ve got cold hands.

Before I can think too much more about the respective temperatures of our hands, Jonah brings them both down, and we slice through LOSERS, and the club cheers like we’ve never lost a round in our lives.

It’s nice, being admired like this, looked up to. Not literally, of course. I’m shorter than most of the club.

“Here’s to kicking butt at Nationals!” Jonah lifts our hands, still joined, and tries to get a chant going: “First place! First place! First place!”

“Attaboy!” Adwoa claps his shoulder. “Keep that energy going! The resolution for Nats is out tomorrow morning.”

“Wait. The resolution is coming out tomorrow?” Isn’t that awfully soon? We’ve only just finished worrying about State. Adwoa is too busy to answer me, mobbed by cake-hungry students.

“Is it chocolate or vanilla?” says Tyler, one of the juniors, squinting at the cake through his funny frameless glasses. “I can’t have any if it’s chocolate. I’m allergic.”

“You’re allergic? To chocolate?” says Ava, a freshman who doesn’t quite clear five feet. “How do you even live?”

“I got you, Ty. Pure Madagascar vanilla.” Adwoa passes Tyler a slice of lily-white cake. “Y’all know there was an ‘allergies’ line on that permission slip back in September, right? I’m not about to serve up shellfish cake with peanut-butter frosting.”

“Damn,” says Jonah, with a full mouth. A vanilla crumb falls to his chest; I reach out, brush it away. “That’s, like, ninety percent of Pinoy food off the table.”

This is very true. I’m no expert in the culinary arts—my skills run the gamut from Frosted Flakes to instant mac—but I’m over at Jonah’s place enough to know the Cabrera family practically runs on peanuts, fried up with salt and garlic. His mom serves them every time we prep for a tournament at his cluttered kitchen table. I love them. I may even need them.

“This cake is it, Adwoa,” says my favorite soph, Jasmyne, moaning through her last bite. “I’m with Finch. Open up that bakery.”

She reaches out to me, bumps her fist against mine. I’ve never told her, not in so many words, but I think she’s the best debater in the club. She’s only fifteen, but someday, no doubt, she’ll eclipse me, eclipse Jonah, outshine us both. I have a feeling I’ll turn on the TV in forty years and see her perching at a podium, running for president.

“Aww, Jas, that’s so sweet.” Adwoa claps her hands over her heart—and then, suddenly, her gooey smile turns mischievous. “I’m still not letting you out of today’s practice round.”

Jasmyne pouts, but I know she’s only pretending. She sees Adwoa as a kind of big sister, I think—an older Black girl killing the game. She’s constantly trying to impress her. And she loves nothing more than a good off-the-cuff argument. The instant Adwoa turns to the whiteboard, Jasmyne’s pout dissolves. She shoves her empty plate aside, reaches for her pen and notebook. She is on.

“Let’s see . . . today’s resolution is . . .” Adwoa rises, on tiptoe, to render the words in big, black, bubbly letters: This House would enact a carbon tax. “Jas, you’re on opposition, along with . . .”

“Adwoa!” Jasmyne drops her notepad, crosses her arms over her chest. “You always make me argue for the evil side!”

“Mmhmm,” Adwoa hums, capping her marker. “N.A.D.A.’s not gonna let you skip a round if you disagree. Neither can I.”

Jasmyne swings her feet, kicking at the legs of her desk. “But you never let me talk about the stuff I do agree with.”

“ ’Cause you’re smart enough to play devil’s advocate, honey.” Adwoa points her marker into the crowd. “Now, on prop, I want to see . . .”

“I mean, if you only ever defended things you agreed with, debate would be completely pointless.” Tyler’s voice is a little more patronizing, a little more duh, than I’d like—especially since we, as a club, have some version of The Devil’s Advocacy Argument, like, once a week. “You’re supposed to put your personal feelings aside.”

“That’s not how it works in real life, though,” Ava offers, her mouth full of cake. No one else is eating right now; she’s either gone back for illicit seconds or started poaching half-eaten slices abandoned around the room. “Like, in the presidential debates, you don’t see the Democrats talking about why the Republicans are so great.”

And then, suddenly, everyone is talking, one voice piling over another. It’s impossibly loud, a cacophony—but, hey, at least we’re all debating.

Adwoa hooks two fingers into her mouth. She blows out a high whistle. “Pipe down,” she commands, and we do, because if Adwoa’s learned one thing in law school, it’s how to drop a convincing order in the court. As we settle, she swings herself onto the teacher’s empty desk.

“Let me ask you something, Miss Jasmyne,” she says, and tucks a couple of braids behind her ear. “Is there anyone you admire who’s done something you don’t agree with?”

“I mean, sure. Yeah. We’ve all got a ‘problematic fave’ ”—Jasmyne’s fingers curl into quotation marks—“or whatever, but I’m talking about people who are, like, straight-up evil.”

“Like who?” Adwoa asks. She holds out her hands, sweeps her gaze across the classroom. “Who is so straight-up evil that we shouldn’t even waste our time asking how they justify straight-up evil?”

“Donald Trump,” Jasmyne answers, instantly. Bravely, too, given that there are more than a few conservatives in our club. I see Tyler raise his hand to offer up some apologia; I see Adwoa silence him with a steely look.

“And how do you know that Donald Trump is straight-up evil?” Adwoa says. “Can anyone give me an example of an especially evil thing that he—”

“When he separated all those immigrant children from their parents,” I cut in, before Tyler can. “Literally tore babies out of their mothers’ arms.”

“Exactly,” says Jasmyne, bringing her palm down on a desktop. “There’s no why there. No excuse. Trump’s just evil. Period.”

Adwoa’s being awfully quiet. I wonder, for a second, if Jasmyne’s g

ot her beat. If she’s about to cede the whole argument. But then she crosses her arms, lifts her head, and levels her eyes at us.

“You know,” she says, “Obama locked immigrant kids in cages, too.”

We’re silent. All of us. No words going her way. Only wide, stunned stares—and a smug look from Tyler.

Jonah’s the first, finally, to speak. “No, he didn’t,” he says—and then, a second later, less confident: “Did he? Actually?”

“Yup. Obama locked all the same brown kids in all the same cages,” Adwoa says, nodding. “Forced them to sleep on the exact same concrete.” She laughs, joyless. “One of his speechwriters tweeted out those photos—you know, with the tin-foil blankets, the chain-link fences? And he was all, ‘This is terrible. Trump’s a monster.’ He didn’t even realize that the photos were from 2014. When he was writing Obama’s speeches.”

I wonder, with a sick, sinking feeling in my stomach, how any of this can be possible. How could this man, who literally put words in Obama’s mouth, not know what those words were propping up? And then I wonder how it’s possible that I didn’t know. I pay attention, don’t I? I read the news. Is that enough?

I look to Jasmyne. She looks like she doesn’t feel very well. Adwoa must see the illness on her face. She gives a kind of sad half-smile.

“Just ask yourselves this,” she says, her voice soft now, consolatory. “If someone like Barack Obama, who’s so much smarter than me, who’s done so much more for the world than I’m ever gonna do—if he could miss something so obvious, what am I missing?”

She pauses. Her fingers drum along the desk.

“Good people get talked into evil all the time,” she says. “I’m just teaching you to recognize evil when it talks—then talk right back at it.”

She stops speaking, but her words linger, heavy, in the air. I feel that sinking sickness, still, but I feel something more, too. Like I don’t have to drown in that feeling. Like I can lift my arms, steel myself, and swim forward. Good or evil, right or wrong—whatever I am, I’m not helpless.

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now