- Home

- Peyton Thomas

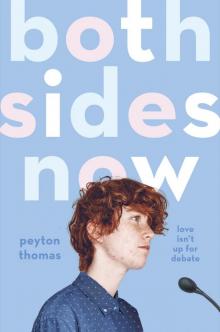

Both Sides Now Page 5

Both Sides Now Read online

Page 5

“And on that happy note,” says Adwoa, with another flick of her braids over her shoulder, “it’s oil tankers versus tree-huggers in fifteen.”

* * *

—

When debate club lets out, the sky is the color of coal dust. A few of my least favorite things about living in Olympia: the prevalence of white people with dreadlocks, the constant threat of seismic catastrophe, and the descent of night, in wintertime, at only four o’clock in the afternoon.

When it’s dark out, I take the bus home, for safety, with a small group. Adwoa’s got the farthest to go, so she claims the window seat, and I settle for the aisle. Behind us, Jonah tosses an arm around Bailey.

“You guys had cake?” Bailey nestles under Jonah’s wing. “And you didn’t even save me a slice?”

He pouts, just a little; Jonah kisses him calm.

“You’d better get that boy some cake,” Adwoa says, giving them a fond look. “Treat him right.”

“Oh, trust me,” Jonah says. “I give him plenty of cake.”

Adwoa laughs, shocked. Jonah and Bailey giggle, too. But I’ve tuned out, eyes on my phone. The Economist’s daily newsletter rolls into my inbox around this time every afternoon, and I don’t want to miss it. Not with the resolution for Nationals landing tomorrow morning. There might be a hint in this e-mail, some newsworthy item we’ll wind up debating. This is what I need to focus on—not romance, not cake. There will be plenty of time for dating after I’ve secured my place at Georgetown. ’Til then: Focus, Finch.

Adwoa pokes me. “Hey,” she says. “You heard back from any schools yet?”

“Still deferred at Georgetown. No word from the others yet.” I can’t help it; I sigh. “I thought the state championship might give me a leg up, but—”

“I know exactly how you’re feeling,” Bailey interrupts, with a sigh of his own. “My final Juilliard callback is this weekend.”

“Fingers and toes crossed,” Jonah says, and he really does lift a hand, cross his fingers. As for his toes, I can really only guess.

“So I’ll be flying out to New York for that,” Bailey goes on, “and then I’m flying out again in June for the Jimmy Awards.”

“The Jimmy Awards?” Adwoa lifts a brow. “I’m not familiar.”

“The National High School Musical Theater Awards,” Bailey recites. You can hear the hope in his voice. “I’ve been before, but this is my last chance. I really want to make it count.”

“He’s being modest,” says Jonah, clearly loving this opportunity to brag. “Bailey’s been nominated for Best Actor twice. Last year, he was a semifinalist. Top four in the whole country.”

Bailey is so pale that I can actually see the blush spreading under his skin. “I don’t want to jinx it,” he says. “I’ve never won anything.”

“Not yet, you haven’t,” Jonah says, and taps Bailey on the tip of his elfin nose. Then he turns to us. “He’s switching it up this year. Taking on a bigger role.”

“Wait—didn’t you play Sweeney Todd last year?” I’m confused. I’ve never been a theater kid, but I know that Bailey’s roles are big ones. Starring ones. “And Jean Valjean the year before that?”

“Yeah! I came to see Les Mis when you guys were sophs. And, Jonah, you played . . .” Adwoa pauses, aiming a thumb at Jonah. “Wait. Don’t tell me. I wanna say . . . M-something?”

“Marius Pontmercy.” Jonah gives Bailey a look so loving I feel embarrassed just witnessing it, like I’ve walked in on the two of them making out. “That’s how I first met Bee. He saved my life. Carried my wounded body through the sewers.”

Bailey drops his head onto Jonah’s shoulder. “We always say ‘Bring Him Home’ is our song.”

“Guys, stop,” Adwoa squeals, throwing her palm over her heart. “I’m getting cavities over here.”

“So what musical are you doing this year, then?” I still have questions. “What ‘bigger role’?”

“Well, this year, I actually got to choose the show.” I can see the corners of Bailey’s mouth tilting up as he speaks. “And I picked Thoroughly Modern Millie. It’s about this flapper who moves to New York in the Roaring Twenties, meets a rich man, falls in love . . .”

“So you’re playing the rich man?”

“No, no. I’m playing Millie.” Bailey’s smile cracks all the way open, a wide moonbeam, on this last word. “We re-named it: Thoroughly Modern Billie. She’s a boy now. It’s a gay love story.”

“For real?” Adwoa gasps a little, then lifts an arm over the seat-backs, shakes Jonah by the shoulder. “Jonah! Why didn’t you try out? You could’ve played the rich man! I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m glad that I’ve got you all to myself for tournament season, but . . .”

She’s asking an innocent enough question—so why is Bailey’s grin getting dimmer by the second?

“Oh, well, you know,” Jonah mumbles, “I was already juggling debate with college apps and family stuff, and I just . . .”

Jonah’s saved by the banner at the front of the bus. It lights up: his stop. After a quick kiss goodbye for Bailey, and even quicker nods to me and Adwoa, he’s hurrying down the corridor, slipping through the doors and out onto the rain-slick sidewalk.

I turn, head over my shoulder, to watch him walk away. Bailey’s doing the same. There’s something deeply unhappy in the cast of his moon-white face. It makes me think—suddenly, weirdly—of that ludicrous thing Lucy said this morning. That I’m, you know, gay. Secretly. And jealous of Jonah and Bailey. If that were true, I’d turn away, wouldn’t I? I’d let Bailey’s sadness fester. I definitely wouldn’t offer my help.

And so, to prove Lucy wrong, I take a deep breath and ask, “Hey, Bailey?”

He meets my eyes. “Yeah?”

I lower my voice. “I know it’s none of my business, but are you guys . . . I mean, are you okay?”

“Oh, yeah,” Bailey says, though his tone seems more oh, no, at least to my ears. “It’s really nothing.” It is, absolutely, something. “We’re just figuring out college and stuff.”

“You two gonna try long distance?” Adwoa asks. “Or is Jonah following you to Manhattan?”

“Yeah, he applied to NYU,” Bailey says, sighing. “And obviously, that would be ideal. But . . . you know. Money.”

We nod. We know. I’ve been agonizing over scholarships for months, and law school’s left Adwoa with a pile of debt the size of a house. She likes to bring it up every time someone in debate club is naive enough to voice an interest in law school—a hard, cold reality check.

“We’ll figure it out, though,” Bailey says, voice bright. “Our two-year anniversary’s coming up soon.”

“Two years?” Adwoa whistles. “That’s a long time.”

Bailey laughs, but he’s pulling away from us, retreating into the blue world of his phone. This is, I guess, a sensitive subject. I may have to keep prodding. But not today. Not now. Adwoa’s turning to me, lowering her voice.

“So,” she says, “we never really talked about your college plans, huh?”

She’s right. Bailey really ran away with the conversation just now, huh?

“I just wish Georgetown would give me a real answer,” I tell her. “I can’t stand this deferral thing. I want a yes. Or a no.”

“You do not want a no. Trust.” She laughs—and, fine, I laugh, too. I could use it. “I’ve been interviewing for a few jobs lately, and . . .”

“That’s exciting!” I lean close to her. “Have you heard back yet? Do you know where you’re going?”

“Well, I may or may not be flying down to Alabama next Saturday,” she says, lifting her hands, inspecting her silver nails, “for a lil’ final-round interview.”

“Wait. Alabama? What’s in Alabama?” As long as I’ve known Adwoa, she’s dreamed of Silicon Valley. What happened to Big Tech? And, besides, if she gets this job

. . . if she moves to Alabama . . . “You’re not coaching debate club next year?”

She chews on her lip. “Remains to be seen,” she says. “I’ve got a few leads up here, around Seattle, but this Alabama job, man . . . I’d literally be freeing innocent folks from jail. Every day, I’d be helping people get out on parole, go back to school, start brand-new lives.” Her voice is soft, tender. She’s talking about this job the way a kid might talk about Disneyland. And then the spell breaks, and she laughs: “It’d be a massive pay cut, though. These people do not have Amazon money. I wouldn’t be able to pay off my loans. Not in this lifetime.”

“But who’s going to take over for you?” I’m being rude, but I can’t help myself. “Here in Olympia, I mean. As coach.”

She curls her fingers into her palm, frowns: a tiny piece of polish is chipping away.

“Honestly,” she says, “if you weren’t heading off to D.C. . . .”

I fall away from her. “Don’t jinx it.”

“I’m just saying,” she says. “You’d better coach a team of your own someday. You’d be great. Those kids? They love you.”

“Thanks, Adwoa. That means, um . . . it means a lot to . . .”

That banner at the front of the bus flickers on. We veer to the curb, come to a halt. I reach for my backpack, wishing I’d found better words, something beyond the obvious thanks. I want Adwoa to know how much it means, her faith in me.

“Get a move on, Finch,” Adwoa says, hugging me tight. “I’ll text you the resolution for Nats first thing.”

And then, after giving Bailey a brief nod, and getting a friendly wave in return, I step unsteadily off the bus, into the rat-gray rain.

Have I mentioned that I hate the rain here? Hate it. Just hate it. Can’t escape it. There are entire months in Olympia where my socks feel like they’ll never be dry.

As I walk up the path to my front door, this is how I console myself: Just a little more rain, Finch. A few more months of rain, and you’re free. You can fly away to the other Washington, the one with seasons. Then your life will begin. Your real life.

I climb onto the porch, fishing my keys out of my pocket. My parents are audible through the door, lurching into something that sounds like another fight. I’ll have to be quiet when I turn the handle. Quieter when I slink down the hallway that always smells like wet dog, although we don’t even keep plants, let alone pets. Quietest of all when I close the door to my own room, to keep my parents—and their fights—at bay.

* * *

—

At a quarter after midnight, the time blinking bright through the black from the clock on my nightstand, there’s a knock at my door. I lift my head from the pillow. A beam of weak light floats into my room: Roo, stepping carefully inside.

She moves on tiptoe, slowly, although she really doesn’t have to. Our parents are in the kitchen, screaming so loud I’d be stunned if they can hear a single thing we do. She’s got a video game in hand, deployed as a flashlight, and blankets, too. A whole mess of them. If Mom and Dad insist on waging war all night, we’re better off huddling in a blanket fort than struggling to sleep in our own separate rooms.

I lift a blanket, flicking my wrists as it flows out into the air, a long wave. Through the walls, Mom’s yelling something about “fifty thousand dollars a year, Mitch! What’s your plan? I sure as hell can’t send him to school on my dog-shit salary.” I wince. This is my least favorite flavor of familial fight: one where I’m the offstage star.

“Because he couldn’t just go to a fucking state school!” Dad’s shouting, too—just as loud, twice as venomous. “No, he has to go all the way across the country and pay out the ass to get something he can get for free right here!”

Roo, pinning a blanket to my desk beneath a heavy trophy, gives me a tortured grimace. I see her mouth form yikes, but I don’t hear her, because Mom is yelling: “He’s a fucking genius! He deserves a good school!”

I’ve seen enough of my parents’ fights to understand: This is no compliment. It’s bait. If my dad takes it? If he goes, No, he’s not a fucking genius, or No, he doesn’t deserve it, the fight will no longer be about money. It’ll be about me. Whether my parents love me. Who loves me more.

And so, for the sake of my own sanity, I think I’m better off tuning out tonight.

What a profound relief to curl up with Roo under all these draping layers of cotton and wool. I turn my pages. Roo’s thumbs tap her screen. I munch on my late dinner, a cereal bar. We make a rhythm, the two of us, with these little movements. I choose to focus on these sounds, instead of the argument pushing faintly through the walls we’ve built. I feel lulled. Safe. I lose track of time, and I’m surprised when Roo lifts her head.

“Hey, Finch?”

I look up, blinking at her in the dim light. “Yeah, Roo? Everything okay?”

“Does it ever bother you?” She gnaws on her lip, not meeting my eyes. “When they talk about you like this?”

The answer, of course, is Yes, it does bother me, very much. But I know that these fights aren’t really about me. Not all the time, anyway. They’re bigger than I am, usually. They’re about the biggest thing of all: money.

“Well, Mom and Dad, they’ve been under a lot of stress for a long time,” I begin. “Dad being unemployed, Mom’s newsroom getting whittled down, I mean . . . none of that has anything to do with me. Or them. Or any of us. It’s not their fault that the government won’t . . .”

“Finch, seriously? Can you please be a human being? For one second?” Even in our low light, I can see the frustration on her face. “Instead of going off about politics?”

“The personal is political.”

She groans. A curtain of black hair falls over her eyes. “Man,” she mutters, behind this veil, “I’m really going to miss your nerd ass next year.”

“My nerd ass?” I can’t help it; I laugh. “Sorry—how many hours have you logged playing Mineshaft?”

“It’s called Minecraft, and I think you know that.”

“Sorry, sorry. I meant Fortwatch.”

“Finch.”

I’m still laughing: “Overnite?”

“Okay. That’s enough.”

She throws her game aside, comes at me on all fours. I lift my book up, a makeshift shield against the tackle I’m sure is coming. It never does. Roo, with a small, scared sniffle, is collapsing into my arms, going limp in my lap. I’m so startled that it takes me a second to lift my hands, pull her to my unbound chest. Roo, usually, isn’t down for physical touch, let alone a full-body cuddle.

“I wish you weren’t going away for college.” Her voice is quiet, almost vanishing in the folds of my pajamas. “D.C.’s too far away. You should stay here. Live at home.”

I rock her, gently. “But where would I go to school?”

“Evergreen,” she says. “Lucy’s always talking about it.”

My turn to roll my eyes. “She’s roped you into her conspiracy, huh?”

“You could get an apartment with her and I could come and live with you guys,” she says. “I wouldn’t have to listen to them yelling at each other every single stupid night.”

“Oh, Roo.” She’s heavy in my arms. “I have to go away to D.C. I just have to. But it has nothing to do with you. Promise.”

“It does have something to do with me,” she insists. “What happens if you leave? I won’t have anybody.”

She’s right. I know she is. Who does she have without me? The pixels on her screen?

“Well, listen: Three years from now, you’ll be in college, too, and—”

“Oh, I’m definitely not going to college.” She snorts. “My grades are crap. And, plus, you don’t need a degree to be a game dev.”

“Okay. Fine. No college. In three years, you can move out, and start making your own games, and . . .”

“Right. Great.

Three more years of trying to sleep through all this screaming. I wish they’d just give up and get a divorce.”

“Ruby!” Her real name rushes out of me. “You don’t mean that. You don’t actually want—”

“Maybe I do!” Roo’s like me—she hardly ever cries—but I can see she’s on the verge now. “It’s been, what, a year? And he’s not even looking for a job anymore! He just sits on the couch and he . . . he . . .”

“He’s almost sixty,” I interrupt, gently; I can feel her running out of steam. “It’s hard to find a new job when you’re that old.”

“So what does he do, then? What do we do? Seriously, Finch: When’s it gonna get easier?”

I have nothing to say. Nothing. At least I can tell myself that I’ll be out of here in a few months. But what about her? How is she supposed to endure this? All I can summon are little niceties, useless ones: Hold on, hang in there, keep your chin up. But I’d rather say nothing at all than give her something so empty.

“I don’t know, Roo,” is what I land on, finally. “Let’s just go to bed. I need to get some sleep.”

“Fine,” she says, huffily, but she settles down as we pull the blankets around our bodies, wrap ourselves up. Even now, after an argument of our own, we both know it helps to have someone nearby. A person who loves you. Who won’t leave.

And yet, when Roo rests her little head on my shoulder, it’s all I can think about: leaving.

chapter four

Next morning, all morning, I feign calm as best as I can. A little more shut-eye might’ve helped in my battle against nervous wreckage—thanks, Mom and Dad—but nothing would’ve kept me from panicking about the incoming Nationals resolution. Especially after Adwoa’s text comes through on the bus to school: res dropping @ 11:30 AM, b ready, followed by a helpful YouTube link: Europe—The Final Countdown (Official Video).

When the hour—well, the half hour—finally rolls around, I’m trapped in the back row of calculus with Mr. Mah. Emphasis on trapped. If Mr. Mah sees me using my phone, he’ll take it; if I don’t read the resolution at precisely 11:30:00 AM PST, I will spontaneously combust.

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now