- Home

- Peyton Thomas

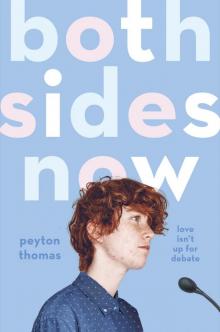

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now Read online

DIAL BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

First published in the United States of America by Dial Books,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2021

Copyright © 2021 by Peyton Thomas

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Dial & colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thomas, Peyton, author.

Title: Both sides now / Peyton Thomas.

Description: New York : Dial Books, 2021. | Audience: Ages 14+ | Audience: Grades 10–12 | Summary: “A transgender teen grapples with his dreams for the future and a crush on his debate partner, all while preparing to to debate trans rights at Nationals”—Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021360 | ISBN 9780593322819 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593322833 (epub)

Subjects: CYAC: Transgender people—Fiction. | Debates and debating—Fiction. | Love—Fiction. | LCGFT: Novels.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.T46546 Bo 2021 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021360

ISBN 9780593322819

Cover photography © 2021 by Miles McKenna

Cover design by Kristie Radwilowicz

Design by Jennifer Kelly, adapted for ebook by Michelle Quintero

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

For Lena,

my best reader, my truest friend

This novel was written on the ancestral and contemporary territories of the Mississaugas of the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Huron-Wendat, and the Dakhóta.

The cover of this book draws from the transgender pride flag designed in 1999 by Monica Helms, a tireless advocate for the rights of trans people, especially trans veterans and servicemembers.

contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Acknowledgments

About the Author

chapter one

“Sorry—we’re the Soviets? You and me?”

“Come on, Finch: When have I ever steered you wrong?”

He’s got a point. In all our years of debating together, Jonah Cabrera has only steered me right. In my bedroom, back home, there’s a bookshelf that groans and sighs and threatens to split under four years of blue ribbons and gold medals. It’s an inanimate testament, that shelf: Listen to Jonah, and you, Finch Kelly, will go far.

Still, I’m skeptical. “You want us to role-play as Stalin’s cronies?”

“Oh, no. Not his cronies.” Jonah swivels to the blackboard, scrawling his points in white chalk. “It’s 1955. Stalin is six feet under. The Cold War’s getting colder. Eisenhower just rolled out the New Look.”

I watch him, hunched over my desk and chewing hard on a yellow No. 2. “Remind me what the New Look was?”

“More nukes, more cove-ops,” he says, standing tall, sounding sure of himself, “and way more American propaganda getting piped past the Iron Curtain.”

“Got it.” I pull the pencil—now a beaverish twig—out of my mouth and take some notes. I won’t lie: He’s selling me. “Keep talking.”

In ten minutes, the two of us will stride out of this classroom and onto the Annable School’s Broadway-sized stage. We will stand before hundreds of spectators, and we will argue, in speeches lasting not more than eight minutes, that every nation on Earth—no matter how rich, poor, or prone to the incubation of terror cells—deserves endless nuclear weaponry.

Do we actually believe this? God, no. Least of all Jonah, the clipboard-toting, signature-gathering student-activist bane of our local power station’s nuclear existence. Among the many buttons presently dotting his backpack, I can see a little one, the color of sunshine, reading: NUCLEAR POWER? NO THANKS! But still, he stands before the chalkboard, doing his utmost to build the case for Armageddon.

“Both teams—the U.S., the U.S.S.R.—they’re fully ready to plant mushrooms all over the map,” says Jonah, with a grand sweep of his arm across the chalkboard. “And the only reason they’re not raining burning hell all over the planet . . .”

“. . . is mutually assured destruction.” I glance at my stopwatch: eight minutes left, scrolling faster than I’d like. “This idea that the only defense against nuclear weapons . . .”

“. . . is more nuclear weapons,” Jonah says. “Because why hit the Russkies when you know they’ll hit you right back?”

As he says this to me, Jonah scribbles a series of suggestive illustrations on the blackboard: smoke, flames, innocent civilians disintegrating into radioactive ash.

If the whole Greenpeace thing falls through, he might have a future as an artist.

Of course, if either of us wants any kind of future at all, we’ll have to go to college first. And if we best the Annable School in the final round of this tournament, the North American Debate Association of Washington State will award us an enormous, gleaming trophy—one that would look great on college applications and, more urgently, on scholarship applications. Jonah’s mom is a registered nurse. My dad’s on his sixth month of unemployment and his seventh step of Alcoholics Anonymous. Neither of us can afford to shake sticks at this particular hunk of golden plastic.

“Okay, but, Jonah, Annable knows exactly how to refute that case.”

“Not if we run the case in the 1950s,” Jonah pleads. He’s literally a blue-ribbon pleader; he is very convincing. “Come on, Finch. Time travel? Ari is never going to see this coming.”

He’s talking about Ariadne Schechter: the Annable School’s prodigy of a debate captain, my worst enemy, my arch-nemesis, the freshwater to my salt. I despise her. I truly do. For so many reasons. Her noxious lavender vape fumes. Her unironic love for one milk-snatching Maggie Thatcher. And, not least of all, her early admission to Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. I settled for a purgatorial deferral letter. I’m still upset about it.

I think I’d be less upset, mind you, if Ari’s dad hadn’t donated forty million dollars to erect the Schechter School of Sustainable Entrepreneurship on a high cliff at the edge of campus.

But I can’t fall into that swirling vortex of a grudge just now. Not unless I want to lose this round, and this state title, and fall even further o

ut of Georgetown’s good graces.

“This ‘pretend to be commies’ angle is definitely . . . creative.” I’ll give him that. It may be the only thing I give him. “I’m just worried it’s too creative. Rule-breakingly creative. The kind of creative that’ll send Ari whining to the judges.”

“Okay, point one: You’re never not worried,” Jonah says, perching now on the teacher’s broad war-chest of a desk. He gets like this when he’s antsy—pacing, snapping his fingers, sitting on anything but, God forbid, a chair. “And point B: You know we need to spice it up this round. End of the day. End of the weekend. Everyone’s five seconds from falling asleep.”

“You included, apparently,” I say. “You just said ‘point one’ and ‘point B.’ ”

“Did I? Damn.” He flashes me a sheepish grin, and then a yawn, his arms flying high above his head. “Guess we need to get creative, then. Wake ourselves up”

“By arguing the whole round in Russian accents?”

“Who said anything about accents?” he says, all innocent.

“I saw you in The Seagull last semester, Jonah. I know you’re dying to flex your dialect work.”

“But . . .”

“Not the time,” I tell him. “Not the place.”

“Fine. No accents. Serious business only.” Jonah, still fidgeting, drums his knuckles against the top of the teacher’s desk: sturdy antique oak, the furthest possible cry from the particleboard and plastic of our own Johnson Tech, ninety minutes away on the outskirts of Olympia. “If we go with the standard case here—like, define ‘this House’ as NATO, or whatever—we basically have to argue that more nukes are a good thing.”

“Right. Hard case for anyone to make. Especially you, tree-hugger.”

“But if we set the debate in the Cold War? Cast ourselves as the Soviets? Make Annable argue for the U.S. of A.?” Rocking to and fro on the desk, he disrupts a decorative apple—World’s Best Teacher, etched in the glass. It teeters. I hold my breath. “We don’t have to hash out all the boring, entry-level arguments,” he says. “We don’t have to touch M.A.D. We can run a more historical case. Talk about communism.”

The apple steadies itself. I exhale.

“And capitalism,” I say, and sit up straight, and snap my fingers. “And the Truman Doctrine, and HST, and . . . oh, oh! If we can link that last one to de-Stalinization, we could even . . .”

His hand finds my wrist, halting my Ticonderoga.

“Knew I’d get you on board.” He winks. “Comrade.”

* * *

—

I’ve never met a president, but when I step out onto that stage, I can imagine, just for a moment, how it feels to be one. I am five feet and five unremarkable inches tall, with a thatch of disobedient red hair that falls somewhere between Chuckie Finster and just plain Chucky. I don’t get to feel like a president all that much.

But here, beneath the tremendous light-rig of the Annable auditorium, staring into the ocean of the audience and soaking in their applause, I feel like I could do . . . I don’t know, anything. Deliver the best speech of my life. Cinch the state title. Win a spot at the school of my dreams. Maybe, one day, I could become the first trans person in Congress. None of it—nothing—seems impossible.

I take my seat next to Jonah at the desk reserved for the people arguing yes, nukes, more of them. To our left, at a desk of her own, Ari Schechter is squinting through the bangs of her Hillary Rodham haircut, scribbling a final few words onto her cue cards. She’s paying zero attention to Annable’s principal—apologies, headmaster—who’s standing at the podium, delivering his opening remarks in a throaty Masterpiece Theatre accent. He’s saying things like “free inquiry,” and “open dialogue,” and “the dissemination of diverse perspectives,” and I’m wondering how “diverse,” exactly, the “perspectives” can be, at a prep school that costs $25,000 a year.

“Representing the proposition, from the Johnson Technical High School,” says the headmaster—and it’s very funny, that snooty extraneous “the”; it makes us sound like we belong in a very different tax bracket: “Jonah Cabrera and Kelly Finch.”

I cup a hand around my mouth. “Finch Kelly!”

I’m very proud of my name. I gave it to myself, after all. It’s a good one. But it never fails to trip people up. “Like Atticus,” I always tell them. “From To Kill a Mockingbird,” and then, usually, they get it, and they nod. “Atticus” was my first choice, for what it’s worth, but my parents vetoed it. They were mostly fine with their daughter becoming their son. Less fine with their son strolling around under the bizarre appellation of a second-century Greek philosopher.

“Ah, yes.” The headmaster pushes his glasses up his nose, peers once more at the paper on the podium. “Finch Kelly. My apologies.”

Light applause. A lone, shrill whistle. That’s Adwoa, most likely—our coach, rooting for us from the cheap seats.

“And, of course, representing the opposition: Annable’s very own Ariadne Schechter and Nasir Shah!”

From the crowd: thunder. It’s like we’re at Bumbershoot on opening night, a wave of sound rolling off the audience. This theater is stacked with Annable kids who volunteered this weekend: timekeepers, moderators, tabulators. They are loud. They are many. But they are not the people we need to convince.

I lower my eyes to the judges, that sentry row right up front. They’re stone-faced, not clapping. How do we reach them? Make them love us?

Or, at least, love the bomb?

“And now, to open the final round of the N.A.D.A. Washington State Championship, arguing in favor of the resolution—‘This House would allow all states to possess nuclear weapons’—please welcome Jonah Cabrera!”

Jonah stands. There’s more of that polite, disinterested, away-game applause. But then he steps forward, and he shifts loose the tallest button on his dad’s Sunday-best blazer. And you can feel it: the audience falling, suddenly, just a little bit in love with him.

Understand: Jonah Cabrera is hot. I mean, objectively. He’s campaign-trail handsome, all square jaw and sharp cheeks and warm brown skin that goes almost gold when he gets some sun. Like a Kennedy from Calabarzon instead of Camelot. You look at him, and you want to keep looking. No, no, not just look; you want to listen.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Speaker, honorable opponents, guests,” Jonah says, and then pauses. “Or, should I say: Good afternoon, comrades.”

He tilts his head to the right. This is a private grin, just for me. I smile right back at him. A delicious, dangerous feeling blooms in my gut.

Like we’re breaking the rules.

Like we’re going to get away with it.

“The resolution before us today is, ‘This House would allow all states to possess nuclear weapons.’ ” Jonah clears his throat. Across the stage, the polite calm is beginning to slough from Ari’s face. “Today, we’ve decided to define ‘this House’ as the Security Council of the United Nations, circa 1955, and we’ve defined ‘nuclear weapons’ as . . .”

Ari Schechter leaps to her feet, arm flying out like a bayonet.

“Point of order!”

Jonah could stop talking. He could take Ari’s question.

He doesn’t.

“My comrade and I,” he says, “will be arguing on behalf of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, in the wake of the death of our great leader, Joseph Stalin.”

Ari brings her Gucci loafer down on the stage once, twice, three times: “Point! Of! Order!”

Annable’s headmaster, seated front and center, surrounded by judges, lowers his glasses. He lifts his hand.

“Yes, Ms. Schechter? You called for a point of order?”

“Mr. Speaker,” she says, her teeth a gritted cage, “my opponent has defined the resolution in such a way as to . . . to render this debate . . .” She stops, scowls, shakes her

head, and tries again: “The definitions brought forth by our opposing team are not, I believe, in the spirit of the resolution.”

The judges tilt together for some debating of their own: Is Ari right? Have we broken the rules? Or is Ari coming across like a petulant preschooler throwing a temper tantrum in the Hatchimals aisle at Toys “R” Us?

In a world where Toys “R” Us wasn’t eaten alive by venture capitalists like her dad, I mean.

“Our judges have reached a verdict.” The headmaster, lifting his head from that huddle of judges, sounds—I think? I hope?—sad. A good sign for us. “So long as the definition doesn’t unfairly limit the terms of the debate—and the judges don’t believe that Mr. Cabrera has done so—the team from Johnson Technical is fully within their rights to define the debate in a historical context.”

“But . . . but . . .” Is that a wobble I hear in Ari’s voice? Is she about to start crying? “Mr. Speaker, if you remove the resolution from the post-9/11 epoch, you effectively strip it of—”

“Thank you, Ms. Schechter.” This is one of the judges, a woman with sleek black hair, raising her voice to speak over Ari. “You may continue,” she says, and smiles at Jonah, “Comrade Cabrera.”

The audience—this audience, so full of Annable students, so firmly with Ari and Nasir, so utterly against us—they actually laugh! Out loud! Ari crashes into her seat with murder in her eyes. Jonah turns to me, another tiny, private grin on his lips.

This one says, I told you I’d steer us right.

* * *

—

After the round, which was honestly less of a bloodbath than I would’ve liked, the four of us are ushered into a tiny white-brick chamber behind the stage. It’s what you’d call a greenroom, I guess, outfitted sparsely: a coffee table, a single threadbare couch. I’m keyed up after our near-hour of arguing, eager to sit down and relax. But Nasir is a step ahead of me. He dives vindictively for that single couch and sprawls out across all three cushions.

“Do you mind?” I ask him, tapping a tired foot. “I might like to take a seat.”

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now