- Home

- Peyton Thomas

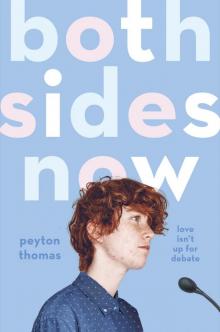

Both Sides Now Page 3

Both Sides Now Read online

Page 3

Speaking of water, I’ve used way too much of it. If I don’t exit the shower soon, Jonah will give me one of his . . . well, no, lecture isn’t the word. Guilt trip, more like. Whatever it’s called when your debate partner pulls out his phone and takes you through the greatest hits: turtle with plastic straw jammed bloodily into nose, seahorse curling perfect tail around Q-tip, skeletal polar bear shambling pathetically over tundra of trash.

Manipulative as hell? Yes. Unbelievably effective? Also yes.

I step out of the shower. Before I can grab a towel, I catch a blurry glimpse of myself in the mirror. The twin peaks of my chest rising and falling. I turn away. I wish—not for the first time—that I lived in a different body.

* * *

—

In the hall, at the mirror, Jonah’s trying—well, failing—to do up his tie. It’s kind of funny: Jonah, who’s been a bona fide boy all his life, can’t pull off a basic knot to save said life. But me, the guy raised in ruffles and bows? I’ve got it down.

Jonah looks jealous as I pull up next to him, tugging my tie effortlessly into place. “How are you so good at this?”

“I practiced the Windsor knot ’til my fingers bled,” I tell him. “Trying to hide the fact that I don’t have an Adam’s apple.” He laughs. I beckon him closer. “Come here. Let me work my transmasc magic.”

He turns to me. The ends of his tie hang long and loose. “Do your worst,” he says as I take one end—stripes, blue and red—and the other—white, studded with a golden starburst—in my hands.

“What’s this pattern?” I ask. “I want to say the Stars and Stripes, but the colors aren’t quite . . .”

“Yeah, no, it’s the flag of the Philippines,” he says. “My dad gave it to me for this tournament. I wanted to pull it out tonight as, like, a very subtle middle finger to the judges who look at me and think, ‘No way this kid speaks English.’ ”

I know exactly what he’s talking about. It happened more when we were younger—ninth graders, newbies. But even now, with our shelves of trophies, we encounter the occasional judge who frowns when Jonah enters the room, before he’s even begun to speak. Or a moderator, maybe, who reads the rules just a little too slowly. Sometimes we’ll even get an opponent who compliments Jonah, during the courteous round-concluding handshakes, on his lack of an accent.

“You’re better than all of them.” My hands go still on his tie. “You know that, right?”

I look up, waiting for a smile. A nod. Something to let me know he understands me. Instead, he says, “I’m sorry.”

I frown. “Sorry for what?”

“The Soviet thing,” he says. “That’s what sank us. And it’s my fault. A hundred percent. I take full responsibility.”

I look down: my hands, his tie. I can’t meet his eyes. How, how does he think the loss is his fault? It’s mine, I think, my fault, instead of paying attention; I miss a crucial step in the knot, botch the whole thing. The thin tail’s dangling loose, all the way down to his belt.

“Don’t apologize.” I pull the knot apart, smooth down the red and blue and gold. “We lost because I wasn’t ready for Ari’s proxy war argument.”

“No, no. You covered all your bases.” Jonah sighs. “She didn’t have a comeback when you brought up imperial overstretch. Your whole Paul Kennedy spiel was great.”

“Didn’t slow Nasir down,” I mumble, in no mood for compliments. “Remember when he was all, ‘The same Paul Kennedy who made his way onto Osama bin Laden’s bookshelf?’ ”

“God, that was such a dick move,” Jonah says, and shakes his head. “You know what else they found on bin Laden’s hard drive? Like, fifty episodes of Naruto. Does that make Sasuke a terrorist? Wait. No. Bad example.”

“Hold still,” I tell him, because he gets excited when he talks about anime, waving his arms around. “Don’t move your shoulders.” I tighten the knot at his neck. “And don’t blame yourself, either.”

He lets his hands fall to his sides. “I just . . . I know how much this meant to you. Because of Georgetown. And D.C. And . . . everything.”

“Well,” I breathe out, and tug his blue collar. “We can still take Nationals.”

“Damn right, dude.”

We smack our palms together—a high five that feels like a promise.

“Well?” he says. “Ready to go? We don’t want to be late for the banquet. Or the after-party.”

“Oh, I can’t wait,” I deadpan, following Jonah out the door. “Tonight’s the night I finally find out what a party looks like.”

But my pan must have been too dead, because Jonah looks back at me, over his shoulder, with wide eyes.

“Wait,” he begins, slow, trying to figure me out. “Are you serious? You, Finch Kelly, the calmest nerd alive—you want to come with me? To a Nasir Shah rager?”

Am I serious? I don’t know. I was in the shower a long time, talking myself into this party and right back out of it. I could stand here even longer, going back and forth with Jonah, picking over the pros, the cons.

But I’ve been debating all day. I’m tired of talking. And so I shrug, and I give Jonah a single, simple syllable: “Sure.”

“Yes!” Jonah pumps his fist. “You and Ari can finally do something about all that sexual tension.”

I shove him, hard, through the open door. He laughs and shoves me right back. We stumble out into the hall, throwing punches too soft to really land.

* * *

—

We arrive at the party a little less than an hour late. Blame Seattle’s buses. The sky is blacker than black above the sleek steel-gray mansion Nasir calls home, and the festivities are in full, grisly swing. I take a balletic little leap over a puddle of oatmeal-y vomit to get at the doorbell. There’s a terrible sound like a swarm of buzzing horseflies before Nasir throws the door open: turquoise shutter-shades, no shirt. “ ’Bout time,” he shouts. “Ready to get fucked up, my [hair-raising racial slur Nasir’s got no business deploying]s?”

Before I can ask where he’s taking us, or complain about the hair-raising slur, Nasir’s ushering us through a gleaming white foyer into an even more gleaming and white kitchen the size of an airline hangar. He sweeps his arms across a countertop cluttered with glassy alcoholic bottles—and a single dented carton of Tropicana.

“That’s for me,” I say, and pour myself a tall orange glass.

“Yo, what the hell?” Nasir grimaces at my juice. “You’re drinking straight mixer? Who does that, man?”

“Don’t worry, Nasir,” says Jonah, hand around the neck of a green-bottled beer. “I’ll drink enough for the both of us.”

“Won’t you get all red in the face, though?” Nasir asks, sincerely. “Since you’re Asian? Or is that just chicks?”

Jonah takes a deep breath—a long one, almost exactly to the count of five. “Nice chatting, Nasir.” And then, before I can protest, or beg him to stay, he’s gone.

He hasn’t left me alone with Nasir. Not quite. There are maybe fifty people packed into this kitchen—debaters I recognize, volunteers I don’t. The girls are in the same slinky stuff they wore to the banquet, and the boys have pulled their ties loose, rolled their sleeves to their elbows. They’re pouring beverages, belting off-key to pop songs I can’t place, carrying on drunk versions of the arguments we’ve been having all day. They look at home here. Comfortable. Like the leap from podium to party is the most natural thing in the world. Where does that confidence come from? And where can I find some?

Nasir nudges my side. Lucky me. In this whole, wide room, I’m his only conversational target.

“So, what’s with the O.J.?” he says. “Why don’t you drink?”

I hit Alateen meetings with Roo every week. I know exactly how to handle this question. “Well, not many people know this, but alcohol causes cancer,” I tell him. “The World Health Organization a

ctually classes it as—”

“But you’re Irish, right?” He ruffles my red hair. “I thought you guys loved this shit.”

Seeing as we’re at a house party in the twenty-first century and not, like, Ellis Island, the abject Hibernophobia catches me off guard. Alateen didn’t prepare me for this one. I have no idea how to answer him. And before I can figure it out, I hear a familiar voice: “Fuck’s sake, Nas. Leave the ginger alone.”

I turn to see Ari Schechter at the tap, filling a glass slowly to the brim with water. Unlike every other girl in the room, she didn’t dress for a party. She didn’t even change out of her uniform. She moves through the crowd to us, plaid skirt swaying. Does she know how strange she looks? How out-of-place? Does she care?

“Rodham!” Nasir crows, thumping her broad back. “Thought you weren’t coming out!”

“I never pass up a victory lap.” Ari grins at me, smug. “How you feeling, Finch? Didn’t see that verdict coming, huh?”

Remind me: Why did I think this party would cheer me up?

“And we’re gonna hit you again at Nats!” Nasir lifts his bottle, lets out a jubilant shout: “Bé salamati!”

I don’t join his toast. Neither does Ari.

“Teams from the same state don’t debate each other in regular competition at Nationals,” she says, all matter-of-fact, “which you’d know if you ever opened my emails.”

“Ugh! Don’t kill my buzz!” Nasir shuffles back, spilling beer. “This is a party! I gotta find me some Pootie Tang!”

I look at Ari, baffled, as he caroms out of the kitchen. “What’s he talking about?” I ask her. “Pootie Tang?”

“He means poontang,” she says, and sighs. “Derogatory slang for the vagina. From the French putain, or prostitute.”

“Oh,” I say. “I see.”

We both go quiet. Ari sips her water. I sip my juice. There’s a feeling, as the party flows around us, like we’re stuck at the kids’ table during a family gathering. Everyone else is having abundantly more fun than we are. Just like that, we’re not arch-nemeses anymore—only the two most boring people at this party.

“So, hey,” she says, leaning into me a little. “About that thing in the greenroom earlier.”

I give her a sidelong look. “When you accused us of cheating, you mean?”

“I was out of line,” she says. “I mean, sure, I didn’t love you guys setting the debate in the Soviet Union. But also, like . . .” She sighs, shrugs. “Fair play?”

“Wow.” It’s almost an apology. I’m impressed. “Are we having a Camp David moment?”

“Oh, no.” She laughs, falls away from me, shaking her head. “Not at all. We fully deserved to win. I concede only that my hissy fit was a bad look. Unsportsmanlike.” She pauses, tapping the rim of her glass against mine—a tentative, non-alcoholic toast. “So: No hard feelings?”

“Oh, no.” I pull my glass away. “My feelings are very hard.”

Her dark eyes go wide, and she says, “Um,” which makes me realize what I’ve said, which makes me open my mouth and go, “Not . . . not like . . . I didn’t mean . . . I wasn’t trying to, uh . . . to like, seduce you, or . . . or anything like . . . like . . .”

“No, yeah,” Ari giggles. “That was very clear from your complete and utter lack of game.”

“I have game!” I step forward, spilling a sip of orange juice on the floor. “I definitely have game!”

“Totally,” she says. “Spilling orange juice? Tried-and-true seduction tactic.”

“That was an accident.”

“Well, I’m still waiting for the receipts.” She sips coolly from her tap water, lifts a suggestive brow. “Some proof of this alleged game.”

I start to speak—“What are you . . .” but before I can even land on talking about, I realize: Ari might be hitting on me.

I mean, I think she is. Was Jonah right? Is there . . . tension between Ari and me?

I turn away from her. I look at the tiled floor. The clean white walls. The bottles cluttering the countertop. Anywhere but Ari. If I’m right, if she is flirting with me . . . well, that’s awfully suspicious, isn’t it? Not only am I her worst enemy, I’m . . . well, I’m me. Not exactly what you’d call a catch.

In the entire course of my life, I’ve only ever had one girlfriend: Lucy Newsome, a lesbian who laid me off the second I came out as a boy. (The breakup was amicable; she’s now my best friend.) Nobody’s ever flirted with me. Let alone at a party. A party at a bona fide mansion with plenty of bedrooms upstairs.

What would even happen if I ever found myself in a bedroom with a girl? Would she want to kiss me? Touch me? Peel off my clothes? Her hands would find the binder. She’d scream. Reel away from me. Tell all her friends that I . . . that I’m . . .

I need air. I need help. Where the hell did Jonah go, anyway?

“Can I . . . I just . . . I need to go find Jonah. Just touch base.”

“Sure. No worries.” Ari’s got her phone out. I look at her; she looks at the screen. “See you later, I guess?”

I guess? What does that mean? Does she want to see me later? And why am I agonizing like this over Ariadne Schechter of all people?

I don’t know. I can’t say. I need to find Jonah. He’ll know what to do. About Ari. About all of this. Even though he’s gay, even though he’s never been with a girl—he’ll know. He’s confident in all the ways that matter. All the ways I’m not. He knows me. He’ll know how to calm me down.

And so I go looking for Jonah. It takes longer than I’d like. I peer into devastated bathrooms, climb beer-sticky stairs, interrupt no less than half a dozen drunk debates. Real intellectual variety here: A big group over by the pool table wonders where you put all the rapists if you abolish prisons; some guys in line for the bathroom argue about which YouTube starlet is operating the most worthwhile OnlyFans.

I finally find Jonah out on the balcony, facing south against the skyline. The view here’s worth millions: Space Needle, skyscrapers, snowcapped mountains rising through the clouds. He’s a tiny black silhouette against all this splendor.

I’m just about to step through the screen door when I see he’s got his hand to his ear. There’s a glint: a phone. I pause behind the mesh. Should I leave, I wonder? I don’t want to eavesdrop.

Until I hear my name.

“No, no, Finch was flawless. The whole thing was my fault.” There’s a pause. He listens; he laughs. “God, Bee, how do you always know the exact right thing to say?” Another pause—longer, this time—as he listens to his boyfriend’s voice. “Right. Exactly. Not a total wash. We’re going on to Nationals. We still got silver medals.” A puff of breath, visible in the cool March air. “Enough about me, though. How are you? How was your rehearsal? Did you run through your duet with . . . Oh, awesome. I can’t wait to see it. I can’t wait to see you.” He sighs; the hand with the phone falls from his ear.

I’m just about to step forward, join him on the balcony, when I hear a crackle of static. Jonah’s holding his phone aloft, dangling it daringly over the railing. “Can you see it?” he says, and it’s then, only then, that I realize what he’s doing: filming the skyline for Bailey. “Mount Rainier, right there, behind that cloud?” I can’t hear what Bailey says in reply, not from where I’m standing, but Jonah seems touched by it. “I’m so glad you picked up,” he says. “I get so lonely at these things.”

Jonah sounds a little strange, different than he does when we talk. I’ve never heard his voice this low, this loving. It’s so big, this thing he’s got with Bailey. So much brighter than anything I’ve ever felt for anyone.

“I miss you,” Jonah says. He waits a moment; he says, “I love you, too.”

None of this is a mystery to him. He’s figured it out. All of it. He’s in love.

And here I am, a total infant, too afraid to even hook up with a girl at a p

arty.

I retreat, fast, before Jonah can see me. I don’t return to the party. I don’t wish Ari a good night. I shuffle, instead, out a side door, and down a long driveway. And then, alone, on a vacant side street, I climb onto an empty city bus and head to the Holiday Inn.

chapter three

“So, what, Ari said you had no game? And you took that as her begging to bone you?”

“Well, when you put it like that, I sound like an idiot.”

We’re on the bus to school, Lucy and me, her fluffy pink head lolling against the window as she pops a bite of tempeh into her mouth. This is the bacon in the vegan bacon-egg-’n’-cheeses her mom made for us this morning. Lucy’s mom is a renowned restaurateur in these parts, the proprietor of Viva Vegan. I’m no health nut, but I’ve never been one to turn down free food.

“All due respect, Finch, you can be kind of an idiot when it comes to, like, knowing yourself.” Lucy takes another bite of tempeh. “I mean, you thought you were a girl. For, like, a decade and change.”

“No, no. That’s not true.” I sit up straight, wag a finger in her face. “I always knew—I always knew—something wasn’t right. I just didn’t know exactly what ’til I joined the GSA.”

That’s where I first met Lucy, on the first day of seventh grade in a math classroom decked out in rainbow crepe. She was a pink-haired punk even then, her skin studded with temporary tattoos that she’s since replaced with a small army of self-administered stick-and-pokes. I was, and remain, her diametric opposite: small, freckled, and shrinking into myself. I’d been dispatched to the GSA after seeing a school counselor for what I thought, at the time, were standard pubertal issues: feeling my body sprouting; wanting to die about it. Lucy was kind to me, that first meeting, as we nibbled on vegan renditions of the Genderbread Person. When it was just about time to go home, she asked me on a date. Her idea of romance? A die-in on the floor of Jim McDermott’s constituency office. It was love at first act of civil disobedience.

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now