- Home

- Peyton Thomas

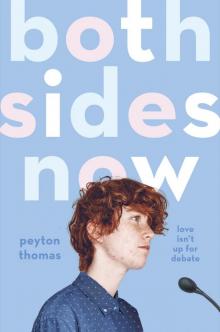

Both Sides Now Page 2

Both Sides Now Read online

Page 2

He doesn’t answer. He shuts his eyes, stretches his legs even longer, and points both middle fingers skyward.

Jonah laughs. “And the award for Miss Congeniality goes to . . .”

“Congeniality? Congeniality?” Ari sounds huskier than usual, pulling generous rips from a Juul the color of Pepto-Bismol as she paces the room. “You guys totally twisted the resolution in your favor, and you . . .” She stops, points her vape squarely at Jonah: “You referred to a genocidal dictator with a body count in the millions as a great leader.”

“Hey, remember when you asked the judges if we were breaking the rules?” Jonah leans against the white brick, giving her one of those broad, easy smiles. “And remember when they confirmed that we weren’t?”

“Exactly.” I’m still in the mood to argue. “You’re just mad you didn’t think of the Cold War angle.”

“You’re right. It never occurred to me to cheat.” She coughs, thick with phlegm. “Whatever. The top two teams at State automatically move on to Nationals. What more do you want?”

Says the girl who wants for nothing—including a spot at my dream school. The one she cheated to get.

“Remind me, Ari: How many buildings at Georgetown are named after you?”

“God, Finch. Get over it.” Even through the vapor, I can see her eyes roll. “It’s not my fault early admission kicked your ass. There were nine thousand kids competing for nine hundred spots.”

“Yo, keep it down.” Nasir pops out an earbud. “I’m trying to bid on this Twitch streamer’s bathwater.”

I ignore him. We all do.

“And you don’t think you had a leg up on the competition, Ari?” I step toward her, into her fog. “Sitting on your ass while your dad wrote check after check after . . .”

Her eyes are still rolling. “He wrote one check, Finch.”

I yelp so hard my voice cracks: “For forty million dollars!”

“Really?” She exhales purply. “I thought it was fifty.”

I sort of lunge at her—to do what, exactly, I don’t know. I’ve never been in a fight, and I’d definitely lose. Ari’s twice my size—taller and stockier. I’m a twig next to her. Lucky for me, Jonah’s cooler head prevails. He puts his hands on my shoulders. He pulls me back.

“Settle down, guys.” He says this to me and her both. “Not the time for a fistfight.”

“No, of course not,” Ari says, shaking her head. “You’d probably find a way to cheat at that, too.”

At my sides, against Jonah’s advice, my hands curl into angry fists. “We did not cheat.”

Just then, the room’s one and only door begins to open: the winged tip of the headmaster’s shoe steps in. Ari fumbles to stash her Juul, Nasir pushes his phone into his pocket, and I shake my fists back into hands. By the time the door’s all the way open, the four of us are standing at attention, model students. If the headmaster notices the violet mist circling Ari, he doesn’t let on.

“Ms. Schechter? Mr. Shah?” He turns to me and Jonah, thinks hard—no paper to read from, not this time. “. . . Others?”

“Mr. Kelly,” I offer, and Jonah supplies, “Mr. Cabrera.” The headmaster smiles falsely, sweeping his arms to the open door.

“Wonderful,” he says. “We’re ready for you.”

* * *

—

“What a spirited, rigorous final round to conclude this tournament.”

The headmaster glances over his shoulder, and grins at Ari—who’s struggling, with ballooning cheeks, to contain a vapory cough—and Nasir. No smile for us, though. Fine. Let him count us out. It’ll be that much sweeter when he rips open that envelope and reads our names.

“Without further ado,” he says, “it is my pleasure to announce the winners of this year’s Washington State Senior Debate Championship.”

His fingers click lightly against the wood of the podium—the one percent’s version of a drumroll, I guess. He takes the envelope in hand. He tears it open.

And just as I’m readying myself to rise to my feet, he says, “Congratulations . . . to Ariadne Schechter and Nasir Shah!”

I don’t rise. I don’t breathe. I can only watch as Ari and Nasir stumble to the front of the stage, stupefied, to accept a trophy the size of my body. I look to my left, to Jonah, only to find that he’s already looking at me, bewildered.

“Second place,” he says, tentative. “Second place still goes to Nationals. Second place is . . . fine. Right?”

Wrong, I want to tell him. Second place is not good enough. Not for me, not for us, and definitely not for Georgetown.

But I don’t answer him. I can’t. For the first time all day, the power of speech has deserted me.

chapter two

“How’d it go, champ? Didya kick some Annable ass?”

Dad’s blurry in the lens of the living room desktop, scratching at the midlife crisis on his chin. He calls me “sport” and “champ” a lot—all in the name of, like, masculine affirmation. I don’t mind it, usually, but I lost the right to call myself a champ today. Lost the right publicly, mortifyingly, in front of hundreds. I wince, remembering; Dad catches it.

“What’s the matter? Why are you making that face?” He’s leaning forward, brow folding, a storm gathering. “Did one of those spoiled brats say something about your clothes again?”

“Is that Finch?” Behind Dad, I see a flurry of flannel: It’s Mom, pulling up a chair, peering at the webcam. “What’s wrong, honey? You don’t look happy.”

When the spotty discount-hotel Wi-Fi allows for it, I usually video-call my folks after tournaments. But I’ve never briefed them on a catastrophe before. I’m not sure how to do it. And I’m not sure I want to, either—deliver bad news to people who don’t need another ounce of it.

Just then, while I’m searching for words, my little sister arrives in the frame. She rakes back her hair—once as red as mine, recently box-dyed black.

“Wait. Did you guys lose?” she asks, disbelieving. I nod grimly. She lets out an emphatic: “Fuck.”

Dad calls out—“Ruby! Language!”—but his heart, I know, isn’t really in the scold. To judge by the dark cloud gathering on his brow, he’s ready to curse out Annable himself.

“Well?” Mom, an arts reporter for the Mountain, knows her way around a tough interview. “Can you tell us what happened?”

Should I lie? Coat the whole thing in sugar, at least? No, no; Mom would interrogate the truth out of me. Better be honest about this, about who I am now: a loser. A person who loses.

“Annable beat us in the final round, yeah.” I scratch at a dehydrated zit on the side of my nose. “Not sure how badly. We won’t know until we get our ballots back.”

“Oh, Finch, sweetie,” Mom coos. “I’m so sorry. You must—”

“What about your college apps?” Dad interrupts. “You were gonna send those D.C. schools your results from State, weren’t you? Try to drum up some extra scholarship dollars?”

Good to know I can always depend on Dad to speak my deepest anxieties aloud.

“Well, we did come in second,” I begin, slowly, trying to smile. “So we’re still advancing to Nationals. That’s something, at least.”

Jonah said this to me earlier, on the stage, when the loss was still fresh. But it’s only now, repeating it out loud, that I realize: Second place is something. Nationals is something, too. Don’t I deserve to be proud of these somethings? At least a little?

“But you can’t go to school in D.C. without a full ride,” Dad says. “We don’t have it like that, kid. We’ve talked about this.”

We have. We have talked and talked and talked. Apparently not enough, though; Dad never misses a chance to shake salt on this particular wound. He and Mom are lobbying me to look in-state, but I’ve got my heart set on the other Washington, the one where progress happens, where good peopl

e fight the good fight, where history breathes in every brick. Georgetown is my dream school, but I’ve applied to American, too, and George Washington. I just want to be there, you know? I want everything the city has to offer.

And, of course, I want to huck a carton of cage-free eggs at Mitch McConnell’s brownstone. No school in the Seattle area will give me that.

“Dad. Please. I know.” I’ve got a bad habit of going single-syllable when he grills me like this. “I do my best. I work hard. This was just a bad day.”

“Everything counts right now,” he says, not listening. “Every grade. Every test. Every tournament.”

I catch his glare. I swallow. I no longer have even a single syllable in me. So I go mute. I lift a hand, find a peeling hangnail. I chew.

“Jesus Christ, Mitch, would you ease off him?”

“What? What’d I do?”

“He just lost his big round. Maybe save the lecture for another day.”

“Well, if he’s got his heart set on these Ivy League schools all the way across the fucking country, he’s gonna have to work for . . .”

“Ughghghghghghghghghghghghgh.” Roo moves close to the camera, peers at me through fingers curled into claws. “They’ve been like this all weekend, Finch. Come home. Rescue me. Please. I’m fucking dying.”

“Okay!” Mom calls out. “That’s it!” She and Dad can fight all they want—all day, all night, apocalyptically—but God forbid Roo drop an f-bomb. “Go to your room, Ruby.”

“Seriously?” Her eyes, made up in clumsy, raccoonish circles, roll and roll. You’re the ones going World War Three in front of Finch.”

“Go. To. Your. Room.”

“Fine. Whatever.” Roo lifts her hands, half hidden in the long sleeves of her hoodie, and rises. “Sorry you lost the round, Finch. Tell that girl from Annable to go suck a—”

“Ruby!”

With that, Roo’s gone, off-camera, before I can blink. There’s a faint echo in my headphones as she stalks heavily into her room.

Mom says, “Sorry about her,” and I tell her, “It’s fine, really,” because if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s my parents confiding in me about how difficult Roo can be.

“Well, hey,” Dad says—spilling salt into my wounds, still, “if you win Nationals, those D.C. schools will open their pockets for sure.”

“I hope so.” Even though I’m bruised from this tournament, I’ve already started plotting for the next one. “There’ll be some stiff competition from those boarding schools out in New England, but . . .”

“Hey, Finch! Shower’s all yours!”

I was so caught up in my call that I missed the bathroom door clicking open. But it’s impossible to miss Jonah emerging—ringed in a cloud of pale steam, towel riding dangerously low. I slap a palm over my webcam. I do not want Mom and Dad to see what I’m seeing.

“Finch?” Mom calls out, disoriented. “You still there?”

“Yep!” I chirp. “Sorry. Just having an issue with the camera.” Jonah bends over a suitcase, his towel slipping even lower. I will not be moving my hand anytime soon. “Can I call you later? After the banquet?”

“Sure thing, sport.” I’ve never played a sport in my life. Dad knows this. “Hang in there.”

“Thanks,” I tell him, and forcefully end call.

The danger is past. Jonah is pulling his pants on.

“Congrats,” I say. “My parents officially know you’ve been working out.”

Jonah laughs and whips his towel at me. I dodge it, but just barely. It meets the mattress with a lewd, wet smack.

“I’m actually super out of shape right now,” he says, which, of course, is a lie, because I saw his biceps flex when he whipped that towel. They are right there, shimmering with little drops of water from the shower. It’s honestly obscene. “No musical this year means no boyfriend busting my ass in dance rehearsals. I’m getting sloppy.”

“Seriously, Jonah?” I lift a hand, gesture at his . . . everything. “In what world is that sloppy?”

It comes out more bitter than I mean it. I just can’t help feeling jealous, looking at Jonah, all lanky, all sun-kissed. Someday, Blue Cross willing, I’ll sculpt my body into something I don’t despise. But all the surgery in the world won’t make me taller. Or smooth my frizzy hair. Or keep my paper-white Irish skin from igniting at the mere suggestion of sunlight.

Jonah’s boyfriend, Bailey Lundquist, the star of Johnson Tech’s drama department—he’s pale, too. Paler, even, than me. There’s something delicate, elfin, about his features. It can be off-putting sometimes, a little alien, but he looks good next to Jonah. Among their Halloween costumes in recent years: a medieval knight and a fairy prince; a swashbuckling pirate and a deep-sea merman; Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen, with Jonah’s beloved mutt, Toto, tagging along in papier-mâché dragon wings.

“Well, hey, look on the bright side,” Jonah says—maybe hearing that bitter note in my voice, maybe trying to cheer me up. “We lost the final round, but we won something way more important.”

“Really?” I perk up. “What did we win?”

“Two tickets to the gun show, baby!” he says, and lifts his arms, curling them like a bodybuilder.

“I hate you.” I toss a pillow at him: right in the abs, bull’s-eye. “Put a shirt on.”

“I was thinking blue for the banquet,” he says, tossing the pillow aside, bending over his suitcase. “And maybe my Hamilton hoodie for Nasir’s after-party. The one that’s like, ‘Talk less, smile more.’ ”

I laugh. “Good advice for Nasir.”

“You know what?” Jonah lifts his head, points. “You should come with.”

“Come with? You? To Nasir’s party?”

“Yes to all three.”

“. . . Why?”

I’ve never been to one of Nasir’s blow-out bashes. You may have already guessed, given that nobody in the history of parties has ever referred to one as “a blow-out bash.” But I’ve heard stories of the carnage: bones broken, babies conceived, tiled floors turned oil-slick with beer and bodily fluid. Not exactly my scene.

“A party might cheer you up,” he says. “Take your mind off the final.”

“Even though the party’s host destroyed us in said final?”

He doesn’t answer; I’ve won. And so I smirk, and make for the shower. “Hope you didn’t use up all the hot water.”

“Please,” he says. “You know I only do staggered showers.”

I do know this, actually, from all our past stays at Super 8’s and Quality Inns. I still like to tease him about it. “Sounds miserable, Greta.”

“You know what? Just for that, I’m timing you while you’re in there.” He taps his wrist, an invisible watch. “Tell you exactly how much water you’re wasting.”

I scowl at him—so I like long showers; sue me!—and step into the bathroom. There’s only a little steam in the air after Jonah’s brief round of room-temperature water torture, but I still have to lift my hand to clear the mirror. When I get a look at myself, I’m surprised: There’s a strawberry-blond shadow sprouting on my chin. It shocks me every time, still. I wonder how I’d look if I let it grow into a beard. Scraggly? Pubertal? Deeply unconvincing?

I sigh. I reach for the razor.

After eighteen months of testosterone and a year of puberty-delaying Lupron, I’m finally able to pass . . . as a thirteen-year-old boy. I get a lot of kids’ menus. A lot of well-meaning strangers being like, “Are you excited to start high school, young man?” I don’t love the “young,” but I’ll take the “man.” It’s all I’ve ever wanted. People look at me, and they think “he.” They think “him.” They don’t think about it.

I do, though. I think about it. Especially when I’m alone like this. I meet my own eyes in the mirror and I pick myself to pieces. Are my cheeks too round? Is my jaw

square enough? Should I cover my acne, or would strangers catch the makeup and think “girl”?

The best way to banish all these questions is to step into the shower, tilt the dial all the way up, and let the jets sear me. This is how I prefer to unwind. Not partying. I’ve never been to one of Nasir’s ragers, but given the sure-to-be-copious amounts of alcohol, and given Dad’s history with the stuff, shouldn’t I steer clear?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s the hot water pouring over me, calming me down, but I’m beginning to think Jonah’s onto something. Wouldn’t some music and movement put me in a better mood? I could avoid beer, couldn’t I? Drink Sprite. Dance, even, if my back stops killing me.

That reminds me: I’d have to bind all night, wouldn’t I? I do not want to put my binder back on. For the first time all day, I can actually breathe: all the way in, all the way out. Nothing is pushing down on my chest, my ribs, my little lungs. The price of this relief, though, is being reminded. Of them. And how obvious they are. And how obviously wrong for me. I’ve got my surgery scheduled for this summer. It can’t come fast enough. In the meantime, though, I bend beneath the showerhead and let the heat strike the sorest spot, right between my shoulders, where the binder’s been pressing all day.

I’m reminded, bending, looking at the long streams of water racing down my legs to my ankles, that I haven’t cried today. Not once. I should be crying. Shouldn’t I? Debate is the one and only place where I’m invincible, where I can talk circles around anyone, about anything. And I lost! I lost the state final! One of those rounds that truly matter. A round that would’ve meant something to the admissions committees of Georgetown and American and George Washington. I’d like to cry about it. Really, I would. I wish I could squeeze my eyes shut and wring everything out: the anger, of course, but the fear, too, and the embarrassment.

This is the thing about taking testosterone, though, the thing nobody ever tells you: Some guys, through some bizarre confluence of biology and chemistry and endocrinology, lose the ability to cry. You still get sad, of course. You still get that hot, familiar ache behind your eyes, and that same old tightness in your throat. But you can’t actually make your sorrow real. The water never shows.

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now