- Home

- Peyton Thomas

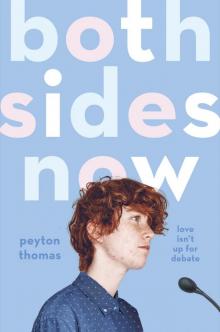

Both Sides Now Page 7

Both Sides Now Read online

Page 7

I wonder, watching them, if anyone will ever hold me like that.

“Jojo!” Bailey shrieks. “Oh my God! Put me down, baby!”

Jonah does eventually set Bailey down, carefully as a china teacup. But his joy doesn’t dim, not one lumen. He tucks a white-blond curl behind Bailey’s ear and he says, “You were stunning today, Bee.”

“I’m stunning every day,” Bailey says, and swats Jonah’s chest. “But you already knew that, didn’t you?”

There’s a brightness about Bailey, even without the spotlight. I feel dull, dingy, just standing next to him. Next to them, I mean. It’s like I’ve walked into a private moment, even though there are dozens of people around, all in careless, messy, post-show dishabille. I turn away from them to face the red velvet curtains bordering the stage. Lifting my hand, I start to trace a little pattern in the fabric. Just something to do ’til Jonah finishes, and finds me, and we can go and get to work.

* * *

—

It’s cold out after the rehearsal. Dark. The sky’s shedding the first tears of a storm as we make our way across the parking lot. Jonah pauses to open his backpack, fumbling for his defiantly yellow umbrella.

“Scale of one to ten,” he says to me, as the polyester canopy blooms above our heads, “how excited are you to fly to D.C.?”

“A hundred,” I say, without thinking. “No, a thousand. A million.”

“We should stop by Georgetown.” Jonah gives me a grin. “Give you a preview of campus life before you move out there in the fall.”

My stomach flips. “Don’t get my hopes up.”

“Why not? How’s any school going to turn down a national debating champion?” he says, and before I can protest—because I meant what I said, about hopes and directions—he points to the bumper of his humble used hybrid. “Hop in. I’ll turn on the butt-warmers.”

A car was never even a conversation in my cash-strapped family, especially after Olympian transit went mercifully zero-fare a couple years back. Jonah was lucky enough to get this car as a birthday gift from his mom and dad last year. It came with the expectation, of course, that he’d use it to ferry his siblings to Little League and Girl Scouts while his dad visited ailing parishioners and his mom worked night shifts at Providence St. Peter. But Jonah’s the type who never drives unless he can carpool, and so, on the days we don’t bus, I find myself in his passenger seat.

Tonight, his eyes are on the road. Mine are on my lap. I’ve got my agenda open, along with a fistful of highlighters—all the colors of the rainbow, an old Pride gift from Lucy.

“So: Seventeen days ’til Nationals. Two debate club meetings between now and then.” I find the yellow marker, drown each Monday in sunlight. “If we can get together and prep every Wednesday and Friday after school, and maybe book some lunchtime meetings at the Green Bean, that’ll bring us to . . .”

Jonah lets out a laugh. A quiet one. I lift my head, curious, and look at him. His eyes have left the road. They’ve found me.

“What? What is it?” There’s something funny about the way he’s looking at me. Actually, no, not at me; into me, more like. I feel myself go stiff. “Why are you staring at me like that? Do I have something in my teeth?”

“Do you remember that first debate club meeting?” he says, just as I bare my teeth at the rearview, searching for parsley. “Freshman year. Adwoa paired us up.”

“She’s got good instincts,” I say, running tongue over teeth, satisfied I’m not missing anything. “How many of those other random pairings are still around, four years on? How many of them went on to Nationals? We owe her a lot.”

“We really do.” He laughs again. “I don’t know what the last four years would’ve looked like without you, man.”

It’s raining now. Hard. He’s still looking at me.

“Thanks,” I tell him. “Eyes on the road.”

He turns his head away from me. The moment, whatever it was—it’s over, I think. I lower my eyes to the agenda in my lap.

“Right. So. If we can swing a few extra meetings on the weekends, that’ll give us an edge, I think, in terms of—”

“I guess I’m just trying to say I’ll miss this.”

I lift my head, startled. “Miss what?”

“Next year, you know,” he begins—and he’s sort of stumbling over his words now, like he’s embarrassed. “When we’re on opposite coasts, and you’re drilling somebody else with your color-coded calendars.”

“Opposite coasts? I thought you were following Bailey to Manhattan. Money permitting, I mean.”

Jonah goes quiet a long moment, chews on his lip. When he speaks again, his voice is soft.

“I got into the University of Washington,” he says. “And I’m going. I got the Doris Duke scholarship. Majoring in atmospheric science, minoring in ecological restoration.”

“And Bailey doesn’t know?” I’m so shocked that I don’t even say it politely, don’t soften it with congratulations. I just bray it out: “You didn’t tell him?”

Jonah turns away from me, wincing. “Not yet,” he says. “But Bailey knows I want to stay close to my family. And he knows UDub’s got, like, the best environmental science programs anywhere.”

“. . . Makes sense,” I say, though I’m reeling: Why is Jonah telling me something he hasn’t told Bailey? “There’s not a lot of wilderness to save in Manhattan.”

“Exactly.” Jonah laughs freely. “I don’t like cities all that much. I need trees. Rocks. Dirt.”

I understand this, of course. I know Jonah. Any weekend we’re not debating, you can find him climbing Mount Eleanor, or hiking out to Sheep Lake, or swimming in the ice-gray water at Priest Point. In another life, he might’ve been a lumberjack, a mountain man. I can see Bailey on Broadway, but I can’t exactly see Jonah in Tribeca.

“So are you guys going to do the long-distance thing?”

“I mean . . . I want to try.” Jonah half laughs. “And it’d better work, or I’ll spiral.”

“Spiral how?”

“Oh, like, party ’til dawn, eat nothing but takeout, fail every single class.” He stops; that half-laugh again. “My mom and dad are gonna get a call at Thanksgiving, like, ‘Come get your son,’ and they’ll show up, and they’ll find me buried in my dorm room under a big pile of Jollibee bags.”

I can tell he’s joking—trying to, at least—but he sounds more worried than I’ve ever heard him. More worried, even, than me on my very worst tears about college, money, the future. What’s going on here? He’s the one who cools me down. I only know what to say next because he’s taught me how.

“I don’t think you have to worry about spiraling,” I tell him gently. “I know you, Jonah. I know how hard you work. I think you’ll be in your element at UDub. Doing what you love.”

“Doing what I love?” he asks.

“Saving the planet!” I throw my hands up. “Patching holes in the ozone! Throwing water on forest fires! Slurping plastic out of oceans!”

“Slurping?” he says, laughing—for real, this time, which makes me laugh, too. We pass beneath a billboard, and a sheet of light rolls over us. But before I can even blink, it’s gone. He’s quiet. We’re back in the realm of dull, dish-watery gray.

“It’s just a big change,” he says, voice flatter—no peaks of fear, no jokey valleys. “A lot of stress. They say college is supposed to be way harder than high school.”

He looks at me like he wants me to reassure him. Like I’ll tell him it’s not true, that college is a breeze. But I can’t. I’m worried about all the same things.

I shrug; he sighs.

“Maybe I’ll feel better when I’m there,” he says. “You could lend me some of your confidence. That’d help a ton.”

“Confident? Me?” What’s he talking about? “My factory-default setting is punishing existential anxiety.”

He throws his head back with another giddy, genuine laugh. “Still, though, you get shit done.”

Do I? All I do, all day, is worry—about my grades, my debate scores, my odds of getting into Georgetown. Jonah’s not like that. Not like me, I mean. He’s better. So much better than me, objectively, in every conceivable way. He’s book-smart, of course, but he stars in school musicals, too, and sits on the student council, and serves dinner to homeless people at his dad’s Filipino American Fellowship every Sunday night. He was homecoming king last fall, for God’s sake. Why would he need to borrow confidence—borrow anything—from me?

We pull into his gravel driveway. He pauses, hand on the gearshift.

“Hey,” he says. “You mind keeping all this between us?”

“Of course,” I say, and I feel a weird, dark thrill. I’ve always been on his team, in his corner; now, I get to keep his secrets, too. “You want to tell Bailey on your own time. I understand.”

“Thank you,” he says, and breathes out. “So much.”

He opens his door, and I open mine, and I follow him up the driveway. There’s a basket of soft sandals in his home’s small, cluttered entryway, right next to the umbrella rack. Jonah’s little blond dog, Toto, yips at my heels as I shuck my shoes and pick out a pair in pristine blue terrycloth.

“Finch!” Jonah’s mom is coming down the stairs in scrubs—crisp, white, dotted with Muppet Babies. “Jonah said you were coming. So good to see you!”

“Hi, ’Nay.” Jonah scoops up Toto, then leans in, kissing his mom on both cheeks. “Need me to make dinner?”

She shakes her head, yanking her dark hair up into a ponytail. “May pinakbet at sinigang sa ref.” The ref—short for refrigerator, I think—catches me off guard. I’m always a little startled by how seamlessly she and Jonah switch languages—mid-sentence, sometimes, or even mid-word. “And I made those peanuts you like,” she says, turning to me. “Bowl’s over there.”

She points through an archway into a living room littered with toys. A bowl of peanuts rests resplendent on the coffee table. It takes all my restraint not to dive headfirst.

“Thank you.” I mean it. “So much.”

“Easy, tiger,” Jonah laughs. He sets Toto down, then squeezes my shoulder. “Sharing is caring.”

He gives his mom a final hug before she heads out the door, and before we head—not slowly, not calmly—to the living room, just about knocking the bowl off the table in our haste to snatch up salty, oily fistfuls.

“I told you Bailey’s allergic to peanuts, right?” Jonah says. “He can never eat these.”

“Really?” He must have mentioned it over the years, but I’d forgotten. I feel a funny pang—real, genuine sympathy for Bailey, deprived forever of Reese’s Cups, the best of Ben & Jerry’s, and Mrs. Cabrera’s finest culinary efforts. “Poor guy.”

“I can’t eat these, either,” Jonah says, sighing like a martyr. “Not if I want to kiss him. And especially not if I want to . . .”

“Okay, okay.” I know where he’s going with this, and I can hear Renata and Benjie, Jonah’s very little and very impressionable siblings, playing with the dog in the next room. “Don’t need a blow-by-blow of your S-E-X life.”

He grins. Wide. “A blow-by-blow?”

I groan and turn away from him and crater my face into the couch’s cushions. He laughs. Laughs! The audacity. My face turns redder; I sink further. There’s a whole ecosystem down here in the crevices of the couch: abandoned crayons, a bent green Slinky, something that might be a shoe for a doll. I’m just emerging, no longer pink-faced, playthings in hand, when I catch a tiny face peering at me through an open door.

“Hi, Renata!” I hold out my palm, my plastic bounty. “Do these belong to you?”

She wavers in the door, thumb in her mouth.

“You can come in, nenè!” Jonah calls out. “Don’t be shy!”

She steps slowly into the room. Her neat black pigtails spring as she moves. “Thank you,” she says, in the world’s tiniest voice, taking the crayons and toys. Before I can even say “You’re welcome,” she’s turning on her heel, leaping out of the room like I gave her an electric shock when her fingers touched my palm.

“She still gets shy around anyone she’s not related to,” Jonah says, apologetic. “We’re working on it.”

I know this, of course. I’m over here a fair bit. So I tell him, “No worries. I’m still shy, and I’ve got ten years on her.”

He laughs, and plops onto the couch next to me before reaching into his backpack for his laptop. “Ready to prep?”

“Hold on.” I wipe my hands on my pants. “Don’t want to get peanut grease on my keyboard.” My computer, unlike Jonah’s, is held together by duct tape; I have to treat it with the utmost fragility.

“No worries. I’ll start the doc.” He opens his laptop and starts to type: “ ‘This House would allow transgender students to use . . .’ ” What was the exact wording, again?”

“ ‘Transgender students in public schools,’ ” I correct him, licking salt from my fingertips. “ ‘To use the bathroom facilities of their choice.’ ”

“Hey.” He turns to me. He’s stopped typing. “Are you . . . okay? Debating about this, I mean?”

My first instinct, my knee-jerk, is to tell him yes, of course; why wouldn’t I be okay with this? I’m a debater. Devil’s advocacy is what I do. What we all do. This isn’t any different from Jonah, with his NUCLEAR POWER? NO THANKS! buttons, arguing for atomic annihilation.

I mean, it shouldn’t be different. I don’t want to be different.

Just about everyone at Johnson is clueless about my being trans. Not Jonah, though. We’ve shared hotel rooms. Shared beds, even. He’s seen me late at night, in my pajamas, binder shucked. There was that one weekend he strolled out of the bathroom we’d been sharing, toothbrush still in his mouth, and asked, “Hey, wuff wiff the rubber dick on the towl rack?” I had a whole entire heart attack. Started apologizing. Launched into this frantic speech on the care and keeping of packers. He just held a hand up. “No worrieth,” he said, and then stepped away, spat into the sink. “It’s a nice dick,” I heard him say, over the flow of the faucet. “You’ve got good taste in dicks.”

I’ve always been grateful for the way he handled that—like it was normal, not something I’d have to apologize for. I’d hate for him to feel like he has to handle me with kid gloves.

“I’ll be fine,” I tell him flatly. “It’s not the first time I’ve argued for something I didn’t believe in.”

Jonah falls back into the cushions, chewing hard on his lip. “You remember that one tournament in Tacoma?” he says. “When we had to be anti–gay marriage?”

“Of course I do.” I still remember how worried he was when Adwoa read us the resolution, how ashen his face looked. “You talked about boycotting the tournament.”

“Right. Because I want to get married, obviously. But then, remember, we started doing research, and we found all those gay activists from the seventies saying, like, ‘we don’t want a world where it’s only okay to be gay if you get married.’ And I didn’t agree, necessarily, but I could see where they were coming from, at least. And we used that stuff to build a case I could live with.” He shrugs, scratches at the side of his nose. “Do you think there’s anything like that for this issue? Like, a pro-trans argument against the bathroom thing?”

I shake my head. “I’m not sure.”

“Well, what about safety? For trans kids, I mean.” Jonah leans toward me. “We could spin it like: Hey, it’s not safe for these kids to use the bathroom of their choice, ’cause they might get bullied.”

“Huh.” For the first time since I read the resolution, I feel that familiar flicker in my chest: hope. “That could work.” I reach for my own laptop. “Lots of trans people are afraid to use public bathrooms. I mean, p

eople everywhere. Even in places that don’t have these laws.”

Jonah’s hands go still on his keyboard. “Are you?” he asks, with the tone of someone who regrets what he’s saying as he’s saying it. “Afraid?”

I open my mouth; I close it. I have no idea how to answer him. We hardly ever talk about my being trans. We definitely don’t talk about my bathroom habits.

“Not . . . really?” I manage, finally. “I mean, not in the last, like, year, at least.”

“Because you, um . . .” His hand works in the air, wrist spinning in circles as he searches for the word he wants. “Because you look like a . . . because you . . .”

I’ll put him out of his misery: “Because I pass?”

“Yes. Yeah.” There’s a nervous flicker in his laugh. “Didn’t know if I was allowed to say that.”

“Oh, you’re not.” I laugh, shaking my head. “Definitely don’t say ‘pass.’ ”

“Got it.” He nods. “I just . . . wanted to know if it made things easier for you.”

“Well, sure. I don’t get weird looks when I go into the men’s room anymore. Although . . .” God, this is mortifying: Who wants to tell their friends how they poop? “I have to use a stall sometimes, and if they’re all full—or there’s only one, and it’s out of order, or whatever—I have to go to the women’s room. Which is . . . not ideal.”

Jonah winces. “I can imagine.”

“Can you, though? You, Jonah Cabrera, strolling right on into a women’s bathroom, going, ‘Sorry, ladies, the little boys’ room was full!’ ”

He laughs out loud. “Okay, no. I can’t actually imagine that. I can imagine the embarrassment, maybe, but . . .”

“Yes! The embarrassment!” I bring a hand down on the couch between us; my palm leaves a crater. “Thank you! This is the trans debate, and it’s the most embarrassing issue possible. It’s not marriage. It’s not adoption. It’s . . .” I lower my voice—very aware, still, that Jonah’s little siblings are playing in the room right next to us. “. . . it’s peeing.”

“God,” Jonah sighs, rakes a hand through his hair. “These conservatives were really like, ‘Okay, how do we make these people look gross? I know! Let’s only ever talk about them in the same sentence as taking a shit.’ ”

Both Sides Now

Both Sides Now